Dalit is the New Political and Epistemic Horizon: An Interview with Suraj Yengde

Dr. Suraj Yengde is the author of Caste Matters (2019); the co-editor of The Radical in Ambedkar (2018), a widely-read columnist for the Indian Express, a scholar of Dalit film and critical thought, a global activist, and the inaugural postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. In this consolidated conversation with Borderlines’ Shaunna Rodrigues, which began in 2018 when Columbia University organised its first Ambedkar Lectures, continued during the Dalit Film Festival in 2019, and online through the Corona Virus pandemic of 2020, Yengde discusses the multiple directions in which Dalit thought, film, and politics have moved in the last two decades.

This interview is divided into four parts. In Part I, On Ambedkar, Yengde explores how Ambedkar marks the intersection between critical Dalit and Black thought; and reflects on the perceptions of the term Dalit within and outside of India. Part II, titled Caste as Method, he touches on some of the most debated ideas in his book Caste Matters. In Part III, Contemporary Politics, Yengde discusses what it means to look at Dalit-Muslim solidarities, Prime Minister Modi's leadership, and the pressing question of political prisoners in India. In Part IV, Dalit Film, he voices his thoughts on Indian cinema, the power of Dalit Film, and the need for platforms like the Dalit Film Festival.

I

On Ambedkar

Shaunna: Columbia University organized The Inaugural Ambedkar Lectures a century after Ambedkar left Columbia. Do you think the Lectures signify a historic moment?

Suraj: Oh, Absolutely! I think Ambedkar is getting his dues back. Hundred years after [he ‘completed’ his education at Columbia University] is also very symbolic, and it is our responsibility to cover those hundred years. Ambedkar lived until 1956, and after that, there has been very little historical analysis about him. [Rather], there has always been more of a political economy approach. We discussed various lenses to understand Ambedkar's political theory in these lectures. What we wanted to do through this is to understand Ambedkar's sophisticated analysis, to churn out the Ambedkar that academic epistemes are lacking.

Shaunna: Why has the becoming of Ambedkar into a global thinker taken so long?

Suraj: I think he was eclipsed. First of all, he was an untouchable, whose very shadow and presence would add pollution to casteist minds. According to the concrete organization of the caste system, he was born and destined to be a person who should have been slogging in fields and farms and working in a landlord’s house. But here he comes and challenges the entire schema.

When he was challenging this schema, he was also challenging the people who claimed to be the custodians of goodwill. That’s why he debunks Gandhi, Jinnah, and the ilk and goes after the Hindu Mahasabha and conservative, orthodox groups. When understanding his ideas, we need to go back to his people. He comes from their rich legacies and traditions. When Ambedkar is proposing something, he is historicizing his presence, and he is talking about the broken tribes. He is giving us a theory of how untouchability emerges. He writes his classic thesis here [at Columbia University], which is one of the most sophisticated statements on caste, and many people are yet to come to terms with it.

Because of all these reasons, his academic entry is not that of a side-kick who can just be put into someone's pocket. He is opposed to the caricatures that frame many of the people he is representing. Because of this, he becomes a threatening object: academic, social, political, economic, as well as one for interpersonal relationships.

Poster for the Inaugural Ambedkar Lectures at Columbia University, November 2018. Source: The Institute of Comparative Literature and Society, Columbia University.

Why did it take so long? Ask Columbia. Columbia University turned a blind eye on Dalits. It should have had a concentrated focus on having Dalits here like Ambedkar was. We would have been able to have some amount of the intellectual career that Ambedkar achieved because it was sanctioned by spaces such as Columbia. But Columbia was selfish in its terms, and so were the people who claimed to represent oriental disciplines – predominantly Brahmins.

Ambedkar is a problem for the oriental and well as Euro-American projects when he critically engages with liberal democracy. He has questions over parliamentary democracy. He is an outright socialist, but he doesn't carry the flag touting everywhere who is championing the rights of the poor and downtrodden, and he doesn't want to fit into the enclosed definitions of a savior. He goes beyond, and then he upholds religion. This is the kind of telos that makes it difficult to fit Ambedkar into any box. He is neither yours nor anyone else's. He's for his people, and when he is, he is extremely real.

Shaunna: Can you tell us more about The Radical in Ambedkar?

Suraj: The project began when the world was commemorating the 125th birth Anniversary of Ambedkar. One of the questions I was struggling with was that Ambedkar was owned by the state which hates Dalits but seems to love Ambedkar. This is what Cornel West calls the “Deodorizing of Ambedkar “ or “SantaClausification of Ambedkar," where Santa Claus comes and gives his gifts but doesn't question authority and becomes fanfare. We didn't want this, of course.

With that in mind, we reached out to scholars in the field, especially young Dalit scholars. We also reached out to the who’s who in the field. This was an opportunity for many who are near retirement to reconcile with the fact that they ignored Ambedkar while writing political theory or teaching at Columbia.

We didn't want to confine Ambedkar to an intellectual ghetto. Rather we wanted people to examine Ambedkar as a thinker. That is how the Radical in Ambedkar came out after two and a half years in the making. It was a pleasant journey. One of the things I also wanted to do was expand into Area Studies – Ambedkar and Africa, for example. We had a chapter asking Can Ambedkar Speak to Africa? Because we were more interested in liberation struggles and how people offer their solutions to this. We wanted this to be more than a hagiography. We wanted him to be critically examined. However, this worked as a first step. The next step would be to fine-tune this examination.

Shaunna: Conversations on how Ambedkar and Africa can be thought of together, or how Ambedkar’s political thought could be expanded by putting him in dialogue with thinkers and movements outside of India, have increasingly gained ground in the last few years. How does Ambedkar mark the intersection between Dalit and Critical Black Thought?

Suraj: Ambedkar is wrestling with the question of Black Peoples’ struggle. He is not looking at the colonial empire through a white gaze. He is very much relying on the archives and struggles of Black folk. And vice-versa. The Black struggle in America is taking notice of Ambedkar – because this is a man who is shining in a black hole where light doesn't exist, where you can't expect anything to shine. Ambedkar doesn't confine himself there. He goes beyond. That's why we see he refers to the struggle in South Africa. He refers to the Black Struggle here in the States. Ambedkar had visitors from across the world – the supposed untouchables of Japan known as Burakumin, their leader Jiichirō Matsumoto knows and visits Ambedkar to discuss future strategies with him.

Ambedkar is deeply invested in what Black Intellectual Thought is thinking. That’s why he writes to Du Bois saying that he has read all his work – this is very important - In 1946. Du Bois has just stepped down from the leadership of the NAACP, and it has been 40 years since he produced The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois was writing about Harlem, the art and beautification of the black body. He was turning away from religion.

The intersection between Black and Dalit as categories itself can be viewed as a concept. But when we think of it conceptually, we also need to pay attention to the empirical evidence of how these communities are performing. We also need to historically ground them. Historians have provided us with historical catalogs of what has happened, but a historicization of these two communities in a comparative perspective has not adequately happened. This requires a serious amount of theoretical thinking.

Ambedkar is rejecting the racial logic, very much like Du Bois did in 1897. He is not willing to accept the idea that caste and race could function together as such because they were skewed categories, but he was taking us somewhere beyond liberatory politics. He was setting the tones that would uproot historical norms. When we read Ambedkar, we need to see these multiple objectives. That way, we can see how Black thought could appeal to different contexts. This has been acknowledged by many African American intellectual thinkers who are reading Ambedkar: Isabel Wilkerson, Cornel West, Kevin Brown. This was also my primary purpose when I went to South Africa to do my graduate studies.

Shaunna: Is there a difference in the way the term Dalit is perceived outside of India and its relevance within Indian Politics?

Suraj: I think Dalit means the same inside or outside of India. Dalit is an emancipatory category. It is a category and not a fixed terminology. Categories have a composite cosmos that have universal appeal. Dalit is not a subdued category. It is not subservient, it is not helpless, it is not dying, and it is not problematizing the oppressor. Dalit is not confined to individual pasts, but it unites people who are oppressed under the casteist regimes. Thus, the appeal of Dalit is an appeal that could bring together the global oppressed.

The Dalit Panther definition of Dalit, which incorporates women folks, landless laborers, oppressed people of the world, placed a condition on the definition of Dalit – it should stand for those who are oppressed by religious hierarchies. The existence of modern, post-enlightenment humanity was the outcome of religious strife – be it Judaism, European Christianity, Islam, and the religions of India. Dalit means love, care, respect too. Untouchables were given nothing when it came to respect and dignity. Our struggle is for respect and dignity. Even when you flaunt your academic credentials, you are still the bootlicking academic. The category Dalit allows you to move beyond this into a dialogue and communication that one needs to have with people who are oppressors. Even if we can't have a dialogue, we will not shelf our struggle.

We believe in the principles of philosophy of great grand love that our grandparents have instilled in us, especially in the principle of sharing love in moments of desperate fragility. What Dalit means to the world is to bring attention to the language of this kind of love and what it means to humanity. The Dalit manages to have a conversation with the oppressor because one has the hope that one day we can strive to overcome thousand and thousand of years of oppression, rape, mutilation of bodies. Every single day Dalits cannot breathe the air one needs for freedom – what she is breathing is the air of dependency and the air of confinement, not of liberation and life. Dalits do that and still manage to maintain their sanity. We have to tell the world that we have to move beyond archaic models

This is what Ambedkar represents. People keep saying it is not radical enough. But if we think about taking guns and bombing anybody, it is against the Buddha’s radicalism and revolution. It is about leading a war without leading the war.

Shaunna: Can the project(s) on and of Ambedkar be separated from activism, and especially one that is driven by global concerns?

Suraj: No. Ambedkar is not your armchair scholar with huge grants and benevolent patronage who produces books. Ambedkar's writing is writing emotion. Ambedkar produces knowledge when he is leading the march to enter a temple. Ambedkar's scholarship comes when he is leading laborers in Delhi or Manmad. It comes when he is joining oppressed people with the labor party. Ambedkar's scholarship comes when he is uniting the women folks with the Schedule Caste Women's Conference in 1940 in Nagpur. Every sentence in Ambedkar's scholarship reflects motion – it is not settled or stagnant, but it is like sitting on a bicycle with him. He's taking us somewhere with him on a journey and the juxtaposition of thinking, as well as moving forward while experiencing it, is in Ambedkar. He dives into a Marxist economic interpretation of theory, explains to the world what he means and what he disagrees within it. He is more Buddhist than any orthodox interpretation of Buddha would entail. He primarily represents the war-field where one is observing the soldier who is aiming at the enemy. Amid callousness, threat, and immediate violence Ambedkar was still able to enact what his people gave him – wisdom.

Shaunna: That is a great response - one that situates Ambedkar in his people, but also raises questions for the Brahmanical nationalist who chooses to be in a state of dissensus with Dalit self-assertion. How does Ambedkar critique nationalism while being anti-colonial?

Suraj: Ambedkar is a recorder of historical crimes. He is cataloging these crimes. He knows his [John] Dewey. He is channeling this thinking around historical crimes through the specific question of what it means for the future. He does not give European regimes a free pass. In his writings, you would see that he appreciates the effort made by European thinkers, but he also holds them accountable. He extends this accountability to some of the leading thinkers – Marx, for example, and he critiques them too. Ambedkar critiques the British regime because they were drafting Indians into the World War. This was not acceptable to him. He goes to London and says this to Churchill. Therefore, he attacks the nuanced forms of degradation that happened both structurally and culturally in India. However, he eventually supports the war against Nazi Germany.

Because he critiques both imperialists and nationalists, it is difficult for Ambedkar to be labeled easily by postcolonial scholars. One has to go to the other catalogs where Ambedkar is talking about multiple things. 'Postcolonial,' which is now quite outdated, and needs to be replaced by Critical Dalit Theory, do a mild injustice to Ambedkar if they only read him with one aim and one target. There are many contradictions. Ambedkar's quest is not to achieve one particular thing but to fix every wrong that has been done so that our future can be less unequal. He asked for a balanced approach to be laid out in the Constitution so that we could rise and live together.

This is not acceptable even for the later neoliberal regime because all they want is to confine people to specific brackets. Neoliberalism has operated through tribal wars. Ambedkar has questioned that constantly. This is where we need to veto other thoughts that claim to speak for Ambedkar.

Shaunna: How important has your journey with Ambedkar been for your academic trajectory?

Suraj: I grew up in a Dalit slum. At one point, I refused to identify it as a slum -- these are Dalit Harlems. Coming to a new place and establishing your universe, inflating your own culture, art, meanings of family and relations, your economy becomes violence, etc. Ambedkar was a household name, and he was the only icon we had. So, we grew up in the teachings of Ambedkar, and he has remained the penultimate guidance. With him, we had someone to discipline us in thinking of broader Ambedkarite politics. We also had Savitribai Phule, who not only guided us but loved and nurtured us. Credit has to be given to rural, semi-urban slum-dwelling Dalit women. Dalit women's love, along with Dalit fathers' love, has bound this community together so strongly. An attack on one is an attack on all. There is a protected space that Dalits have claimed for themselves. However, there are internal fights too, and I witnessed that in its crude form.

I grew up in this environment, which was an extremely fascinating and vibrant environment. Every morning Ambedkarite songs would be played in the viharas. "Ambedkar Buddha Bhim Geetein" as we called them, sung by the excellent Vitthal Umap, Prahlad Shinde, Anand Shinde, Milind Shinde, and many more guided me. It has also been the political charge behind my experiences, which in modern technological language comes to be codified as the self.

For Ambedkar, praxis came first. Many people go to a theory first and then apply theory to praxis. We didn't have this luxury. When we encountered problems, we'd see a citation saying Ambedkar did this, and we'd say, "Oh really?". Ambedkar is also someone who gave us a framework of being critical, and that is why we have to be critical of him too so that we can have more of Ambedkar rather than less of him. Ambedkar very easily speaks to me. Almost every Dalit looks at Ambedkar as a single-handed icon – whatever religion they have gone to, they have maintained this connection. That is why Ambedkar remains a secular character with a strong Buddhist ethic. That's why academia needs to take more notice of him. That is what our quest is. Columbia has failed on this front.

Shaunna: Could you comment on Ambedkar's appropriation by the Hindu Right and by those who are not part of the Hindu Right. How has Ambedkar been made available to different agendas?

Suraj: That is the fascination of a thinker who talks about universal values because universal values are not condensed to space and time but use lateral markers. Universal values of Ambedkar were always available, but casteist academia did not reach out to these. Ambedkar talked about minority rights, the formation of political parties in India, social and legal justice, finance, and the development of the nation. He wrote on representation, the formation of the Scheduled Caste Commission, the making of the Constitution, and finally, Buddhism. Today Deweyans want to claim Ambedkar as a Deweyan. Buddhists want to claim Ambedkar as a Buddhist. Scholars of Marx want to claim the Marxist in Ambedkar, and philosophers want to claim the Kantian in Ambedkar, scholars of Black thought want to claim Ambedkar's epistemology as Black-oriented. Because of this, Ambedkar is available to so many people, especially because he focuses on human oppression. Here I want to emphasize the human because, as Ambedkar pointed out, oppression is extended to those who are not considered human or considered sub-human. Ambedkar debunks this exclusive formula for the human and leverages his position in such a way so that subhumans can be considered to be humans afresh.

Here the Right has an agenda, and so does the Left. If you engage with Ambedkar, you are not going to face a wall. The Right wants to claim Ambedkar because Dalits are a potential challenge to the Brahmanical project. If the Right can't fight them, then they try to assimilate them. The Right has made its enemy it's best friend because they can't kill Dalit assertion. The Left also wants to appropriate Ambedkar because they have also understood that Dalits can be dangerous to their project. The Left movement was built on the backs of Dalits in India.

Who are the working class, laborers, peasants, toiling masses? They have a caste, and the ones who are ready to fight back are Dalits—you put them in any color or any box wherever you will see a rebellion; it is the Dalit essence. They dedicated their stigma to fortify the Ambedkar that the world should know. It is because of their sacrifices that Ambedkar has become an icon available to the larger public. Credit should also be given to the counter-public sphere – Dalit poets, autobiographers, artists, people who perform on stage, those who have performed Bhim Geetein in praise of Ambedkar, and who have made him an immediate point of focus.

II

CASTE MATTERS

Shaunna: Caste Matters is an extraordinary book. It re-centers Brahmanism as the ideology that governs India’s public life. There is an urgency with which the book does this. Why the urgency?

Suraj: This is how it came about. I’m a migration studies scholar. I study African theory – that is why I went to South Africa [for a Ph.D.]. Many people don't know the personal journey behind it [the book]. I was in the UK. I had a job in London and was basically living the life of a human rights lawyer. But I was not satisfied with it because I wanted more answers for my future and that of my community. When I say my future, I tie it with my community. I observed that Africa and Latin America were the spaces that Dalits had not forayed. Africa was important for me because I worked at the UN, and I paid attention to African social and political issues. [At that point] I was very much smitten by the stereotypes of American cinema and culture and their gaze over African people. One day, when I was in London, I decided that I don’t want to do this anymore.

So I started applying for jobs, and I wanted to go to Somalia. But due to security clearance issues, that did not happen. My search took me to the development sector world - I was looking for jobs in the development sector without knowing it was the 'development sector.' I wanted to go to Africa to find out how African people are living, surviving, and fighting, how they imagine politics. It was very important to the Dalit community. Africa is a continent of 54 nations, and that was a huge mass of space that I could cover geopolitically. Everyone was surprised – they asked me why you are going to Africa?

The reason I went was to find this framework as to where one could develop Black and Dalit solidarity. That is where I developed my project. I wanted to study caste among Africans, but the sponsor – which was the Indian government – rejected that project and asked me to work on migration. As a graduate student, you would know that you try to accommodate different considerations because you just want to get your Ph.D. done. I finished that project in two and a half years and got my Ph.D. from the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Then I came to Harvard, and I was really looking forward to connecting with African-Americans, and that is what happened. It really opened my views. I took many classes in African-American history, culture, and literature. I saw that galaxy of scholarship that they have produced, and I was taking notes in my Evernote App. Because I have a Ph.D. in South Africa, it is difficult to get a job in America because America is really Americanized. But in the meantime, I was talking to Henry Louis Gates Jr., and one day, he asked me, "Why don't you come to my office?". I nodded unsurely. Then he continued with a Skip Gates signature pomp, "You know my office. Do come". I was polite and said that sorry, I did not know his office. I think he was slightly taken by surprise. He's a star, an incredible scholar. So I went to his office during office hours. He said, "Listen, I did not know that Du Bois and Ambedkar had such a beautiful connection." And he said, "Tell me, how much do you need to complete your work?" I was not prepared and unable to ascertain what he meant. Then he said, "I'll give you a fellowship, you write that important book. We need to know this story!" I was pleasantly surprised. He gave me a Du Bois fellowship to finish this project. That is when I decided to write Caste Matters.

I wrote a very academic book – these were the issues I was thinking about, speaking, and debating for some years – I thought I should revisit these ideas. I wanted to write what I think was great. If you think it is arrogant – that is your insecurity, and there is nothing I can do about it. As I mentioned, in my Ph.D., I worked on migration. I shelved the Ph.D. I was not a professional caste studies scholar in the academic sense. This meant I had to read many new things. There were some things that I had read for interest earlier that I returned to as I was writing this book, and I thought, damn! This is how, I guess, that Caste Studies came about.

Shaunna: You mentioned criticism of the book. People said that your critique of constitutionalism, as a centre of Dalit political discourse, was not okay, especially given that constitutionalism in India continues to be a powerful counter to Brahmanism as the defining ideology in the Indian public space. Could you tell us more about what you wanted to defend when writing about constitutionalism in this way?

Suraj: Shaunna, there is one thing we need to understand, I come from a family that is below the poverty line. I am the slug from that sludge. It is a very dirty muck that I come from. And I, fortunately, was in a house where my father, who was a peon – a chaprasi. I remember him getting a cheque for INR. 3500 every month – was very interested in ideas. I had Leo Tolstoy's writings in my house, Einstein's autobiography in my house, I had Kanshiram's writings in our house. These were all in Marathi, by the way. We also had Marathi literary giants like Baburao Bagul, Raja Dhale, V S Khandekar, Bhalchandra Nemade, Durga Bhagwat, etc. Our consumption of literature in the regional language was very strong. My dad would also get magazines that were read by progressive people of different castes – but also elite people in Bombay. Nanded is like a small backward town, where my father would get a magazine like Sadhana – a high, cultured Brahman influenced magazine, which was also interested in rationalism, progressivism. So my dad was not just confined to Dalit literature. Rationalism is also where Dalits find their solace. As it turns out, Sadhana is publishing a piece of mine. If my dad was alive, he would be so proud because Sadhana was his favorite.

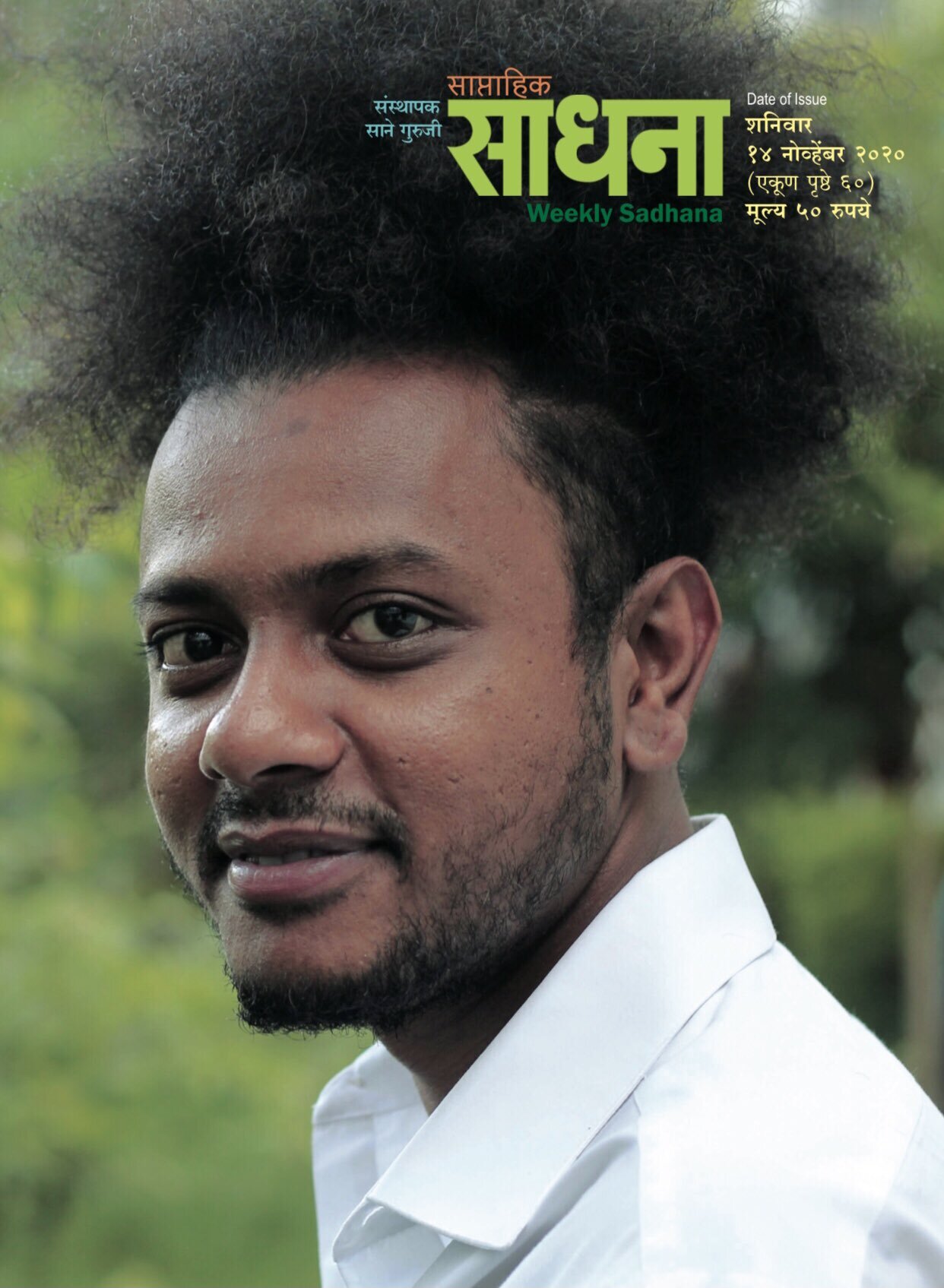

Suraj Yengde on the Cover of Sadhana Weekly Magazine, November 14, 2020. Source: https://www.weeklysadhana.in

I say all this in order to say that I am an accident of an accident. People come from Dalit backgrounds and a lot of poverty. But putting yourself through all of that [the world of ideas] requires a lot of perseverance. I don't know how I do it. But if you have to set a history for the future, then you have to be an oil-presser so that the future community can taste the sweetness of that oil.

Allow me to do whatever I am doing. I have not questioned your way of operating. When I do my work, if you feel like you are being attacked, then maybe that message is for you. But the book is a work of art – I have painted it. The spectator has to feel it. If it hits to the core, you can sit and stare at the piece for days. If it doesn’t, then you can just walk away. Whoever wants to relish these ideas, I’m good with that. Whoever wants to criticize the book, I’m good with that too. But I want to be loyal to my grandmother’s pain, my mother's pain, my fathers’ position, my sisters' securities and insecurities, my brothers’ wilderness. My own degradation. In that sense, this is a flow of ideas. The book is a monument of history and I wanted to be truthful to this time, honest to it, rather a betrayer of the time.

Shaunna: You come up with a methodological category that you call “castegories” – a term that helps one make sense of those who wield and use social meaning or significance. How do we politically mobilize these terms, and how do they extend across religious boundaries as well?

Suraj: When I write about castegories, I mention that this term is not something over which there is exclusive Dalit ownership. The phenomenological understanding of castegories has to go with the very element of caste and how it is categorized. Caste is a fragmentation. Within that fragmentation, there are universal values of each segment. The Brahmanical project in India is to say that I cannot impose values [from one fragment] on the other, and the other can’t impose those values on me. [In this way] They impose a history that belongs to nobody.

My humble opinion on castegorization was to identify how it plays with, or captures, power dynamics because power is very central to castegories. Of course, it exists across other religions and castes. You can find them among Christians, Muslims, among Brahmins too. I did a Dalit take on this because that is my empirical knowledge.

People even said that I was trying to write stories. They didn’t realize that as a researcher, when you go into the field, you take notes. One notices that power has an interplay with culture – these values of power and culture have their own universal appeal. If I belong to one of these castegories, I have a universal appeal say – as a radical Dalit, I look at myself through other radical models. If I was a conservative Dalit, I would look at conservatism as an acceptable model.

So I presented it, and if people read it as a criticism of so and so, then that is how they read it. As an author, I have little right to impose a particular reading on the readers. It is their book now. It has entered their brain cells and is operating within their body. Their actions are mediated upon through how they perceived the ideas [in the book].

I could have written all this by citing Pierre Bourdieu, Fanon, and Ambedkar, and using a lot of academic languages. For example, I wanted to exclusively think through the Greco-European tradition – Socrates, Aristotle, Sartre, Heidegger, Hegel. And my first draft was these people vibing with a Dalit mind. But the message would not have been conveyed. The methodological explanation needs to be offered whenever we approach a Dalit topic. That section [on Castegories], if people read it with a sense of methodological durability, they will get a good sense of how to approach it. Thank you for bringing this us up.

III

CONTEMPORARY POLITICS

Shaunna: India’s government has brought its Hindu nationalism to the fore more strongly than ever. You write about this often in your column Dalitality, arguing, sometimes controversially, that Muslims face the same experiences as Untouchables in today’s India. What are the grounds on which Dalits and Muslims could ally together to form a counter-public to the might of Hindu Nationalism?

Suraj: Very good question. At the ground level, based on my own experience, let me tell you if you look at the spatial arrangements of urban or semi-urban localities in India, Dalits and Mussalmans live next to each other in one corner of these spaces, they are shoved there and juxtaposed to each other. There are two things which work well for them. [First], they eat the same food – same spices, same meat. Second, both are beaten by the Brahmanical social order. They find a kind of solidarity in this.

But this doesn’t mean that solidarity always exists. There are many contradictions. There are many fundamental Mussalmans in India, especially among the poor Mussalmans. People don't like me saying this, especially liberals, who panic when they hear this. Liberals keep writing to me saying, why do you write this? We have huge arguments. But most of these people have no experience when they ask these questions. Most of them live in posh apartments and had Muslim friends whose parents were IAS officers or industrial owners. They hang out in a different sociality altogether. It is only an accident that they and I are talking about right now. Had I been in India, their and my world would have been completely different. They would have looked down upon me, even though they believe in socialist values. Their casteism would not have given me space. I get very intolerant with these people who want to preach in their nascent wokeness.

Why do I say this? It is because the Mussalmans and Dalits have always been with each other, but also ‘at’ each other. The consciousness of Mussalman's in India is very much tied to the Hindu. They don't break the "Hindu" according to caste. When they look at Dalits, they don't look at them as independent Dalits, but they look at them as Hindus. It is not their problem. It is because of the education they have received from Maulanas and Maulvis. Mussalman’s are traitors to the Dalit cause. Now you will say, "How can you say that?" I'll tell you. They go into the mosque, and they pray for Philistine (Palestine), but did they go to the mosque and pray for Khairlanji, Tsundur, or any other massacre of Dalits?

Now I appreciate the liberal argument that Mussalmans and Dalits must come together, but we must also understand that there have been huge local and internal tensions. Who benefits from this? The Brahmins who utilize this to tell Dalits that Mussalmans are traitors of this country. Now Dalits don't have access to brahmins directly, but they have access to Mussalmans – why? Because they are neighbors. I once gave a speech at a Left Forum on the question "Is Dalit Revolution possible?" I said "Not possible! How can you ask this? When the French revolution happened, they stormed the Bastille. For Dalits to go to the center of power, [there are so many hurdles] they are spatially separated from it!" The brahmins have Hinduised Dalits for no reason. In doing so, they misdirected attention towards Muslims.

Now we can talk about Muslims and Dalits. They have always been together on a political front, that I can tell you. But Muslims have also committed mistakes when it comes to Dalit liberation. These [those who commit mistakes] are not 'regular Muslims' – I make a differentiation. These are upper caste 'convert' Muslims. The lower castes – Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, and Other Backward Caste (OBC) Mussalmans, they have the same last names as [non-Muslim] Dalits! For example, if you go to Western Maharashtra, you’ll find a common Muslim name to be Abdul Deshmukh. They [lower castes among Muslims] have retained their unique perspectives. When I critique Mussalman's, I am critiquing the dominant caste convert Mussalmans who continue to be the spokespeople of the Mussalman community in its entirety while fueling the Hindu-Muslim divide, which I say is a farce.

The Hindu-Muslimization of India have helped the dominant castes of both religions. The Sachar Committee report talks about the evident disabilities of the Mussalman – does it relate to the people who came from the Mughals? No! The report refers to local, indigenous Muslims, who were systematically kept apart. Even as one prays in the same mosque, will you [Upper caste Muslims] marry their daughter to lower caste Muslims? Nobody wants to talk about this.

My criticism comes from a very lovable departing point. Do Muslims and Dalits in India need to work together? A 100% yes. How do they need to work together? Within a Bahujan framework, which is possible because Muslims are part of the Bahujan identity. You can be Muslim and still be part of us. I am changing my narrative these days if you have recognized [it]. I am talking to Dalits about this too – there are Dalit Muslims, there are Dalit Christians, and we need to be more open to them. It is a difficult conversation, but I have begun it at my level. I am concerned about my Dalit sisters and brothers who just got a different name and faith, otherwise, our DNA is the same.

Slowly, Muslims also recognize it too. However, what I want to say to them is: first of all, don't call us Hindus. We are not Hindus. Even if you call Dalit Christians, Christians, you are taking away their Dalitness. I am against the so-called 'communalization' of Indian politics only through the religious sense because religion is a makeover of a deep problem that has to do with caste. The caste problem continues by making this seem like a Hindu-Muslim problem.

If one makes it a caste problem, then one can attack caste. One cannot attack religion – who will do it? Attacking religion will not take us anywhere. It will create a religious war. But one can attack caste. It is possible. The ownership of caste has to do with the people who are benefitting from other people. Attacking caste will take us towards its annihilation.

Shaunna: Writing on caste among Muslims and Christians today is still so minimal. The Sachar Committee report told us that Muslim Dalits are the most vulnerable group in India, and this was in 2006!

Suraj: Many used that report to say that Muslims are oppressed. I appreciate that but which Muslims are oppressed? If you say Hindus are oppressed, will you accept that? No, we will say that it is Schedule Castes who are oppressed.

Shaunna: How does one view the nature of the leadership of Prime Minister Modi through the lens of caste? Modi is not a brahmin, but he is often accused of upholding a Brahmanical order. Perhaps Modi could not have become the Prime Minister if the Brahmanical order that we have come to recognize in India’s founding moment in the 1940s was still the same. There is a way in which Modi’s rise to power reflects a transformation in this Brahmanical order. How does Modi, as a leader, continue to uphold a Brahmanical order while simultaneously revealing a transformation in it?

Suraj: This is a good question. Brahmin can be understood in three ways as (i) an identification (ii) a representation, (iii) an individuation. If we understand these three modes clearly, then we can map out the caste framework of how to look at Modi. The caste understanding of Modi is brahmin as representation, but more importantly, Brahmin as an identification. He fulfills these two framings, but he can’t be an individuated brahmin because he is not one. RSS is all three. Can all brahmins be all three? Not necessarily. For example, individual brahmins can choose not to represent Brahmanism – those who are on the right side of the cause.

Modi is the epitome of brahmin identification and representation. His caste is irrelevant here because the representation can be by a messenger. Messengers can always be disposable bodies. Within this messenger job, all he is doing is what his masters are telling him. He has no authority to act individually. He also knows he is a lower caste person. He might be an OBC since 1994 or a Modh Ghanchi (Baniya) -- his original caste, but he’s still lower than the brahmins.

We have to know how this plays out in our own understanding of caste. Modi is going to die as someone who is the prime minister of a country. His legacy is not going to outlast his death. Brahmins are going to make sure that they will get the credit for what he has done. The other OBC’s will get blamed for the wrongs. That has been the tradition of this brahmin system.

If Modi was an individuated brahmin, it would have been a different cause. In the politics of representation and identification, he is living a very myopic reality, where he is identifying himself with the brahmin cause – RSS Dalits, RSS Mussalmans, and RSS Christians are like that.

That being said, what Modi is doing is that he is creating so much chaos that it will take only a few generations of the memorialization of Modi for him to be relevant. They will memorialize him like they did Vajpayee – Vajpayee was no good! But now they say he was a great gentleman!

We need to look at how Modi is going to be a miserably failed OBC, and it will haunt the backward classes for a long time. His memory will come back again and again. Nobody talks about how Modi represents Brahmanical values. They keep saying that Modi is OBC because they want him to be judged through his caste values.

Shaunna: Your co-editor for The Radical Ambedkar, Anand Teltumbde, and other Dalit Activists were arrested this year, under an extraordinary law like the UAPA, on Ambedkar Jayanti for raising their voices against the Bhima-Koregaon case. This happened during the pandemic when lockdowns were being enforced everywhere. The application of the UAPA has not stopped even under the lockdown. What do these arrests, those of so many other political prisoners, and the rampant use of extraordinary laws mean for Indian democracy?

Suraj: This Indian government is continuing British era laws. They are the progeny of the British empire. You can’t claim to be Indian when you are tied to British era tyrannies. That means our ancestors who fought for us; their sacrifice is not valued. Sedition laws were created by the British regime. They were foreigners. They had no sympathy with us. They wanted to exploit and extract whatever they could. They knew they had to leave at some point.

The Sedition laws and UAPA [Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act] are primarily anti-Dalit and anti-Adivasi.

Shaunna: They are anti-Muslim as well.

Suraj: Yes, they are anti-Muslim as well. Many young Muslim kids were languished in jails by the Congress government. But going by TADA [Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act] and POTA [Prevention of Terrorism Act], and especially UAPA – Adivasi's are the largest number to be hit and are disproportionately targeted because they [the government] call them Naxals. Manmohan Singh, instead of saying that India’s greatest internal threat is Naxalism, should have said that India’s greatest internal threat is Brahmanism, operating through its multiple organisations.

You also have to look at the castes of military officers posted in Adivasi areas. Most of them are Upper Castes, and it all plays very well because they don't have empathy. You and I and many others can sit here and just not know what is happening in the jungles where all this is happening. What is a Baniya doing in an Adivasi village? He is giving loans. He is taking generations of wealth from those communities. Adivasis are fighting against this kind of Brahminical oppression, not necessarily against the state. But the twice-born comrades try to place them anti-state.

These laws need to go immediately. It has no place in a democracy. When I make a Dalit-Adivasi intervention like this, it is to highlight their plight in this. Other dominant castes are serving the movement. We have seen it in Bhima-Koregaon as well. People have been put in prison for 180 days without anyone talking to them or trial! This is Guantanamo Bay operating in India.

These are manufactured Naxalites, manufactured anti-nationals, manufactured dissenters. You and I disagree with the government. Are we Naxals now? Also, the government is doing this to suppress Dalit radical movement. Dalits don't want to be Naxals. But by threatening Dalits constantly by telling them they are Naxals, they have removed Dalits from the picture easily. It works for the state to not bring Dalits into the picture here, because if Dalits get involved in this through an Ambedkarite lens, it is going to be a huge problem [for the state].

If you remove these laws, then you will see an active kind of solidarity against oppression. If there is violence, the response will involve violence. If you are raping my mother in front of my eyes, and later you want my daughter to be raped by another person, and then you slit my father's throat, you are not letting me forget that trauma. The Indian state is repeating traumas on Dalits and Adivasis of this country. They want a violent reaction because if there is no violence – this is a simple Foucauldian argument – there is no need for a police state – in fact, for a state at all. They are legitimizing their expenditure on military contracts and militarizing the Indian state. The Right to Information Act doesn't apply in this field, so we don't know what kind of backhanded activities and multi-billion dollar deals are taking place. By regimenting, the everyday life works in their favour to constantly corporalize the bodies of Dalit and Adivasi.

If we do the same in brahmin neighborhoods, then the dialogue will change. This is only operating in Dalit and Adivasi neighborhoods because they are soliciting a certain response.

Kashmiri pandit issue is still relevant today. They don’t want to put down their sacrifices and their lost lives. We respect every life, especially those who have been slain unnecessarily. But look at how the state uses that program of Kashmiri pandits as a representation of entire Hindu oppression. Why does the oppression of Dalits or Adivasis not come to be seen as representative of oppression for entire Hindus?

When Dalit ghettoes were burnt in Bombay, Ramabai Nagar, was it taken as an assault on India? Was it taken as an assault on Hinduism? That itself proves that Dalits and Adivasis have no stake in a brahmin republic. Their issues are not Indian issues. Their suffering and tears are not the tears of every middle-class Indian. What investment is the state putting in them after all this? Giving them breadcrumbs of reservations. Even that is not implemented, and that is where my criticism comes.

Nine thousand jobs are still pending for teaching faculty since the Modi government came to power. All the public sector undertakings which had 29 lakh employees from the Scheduled Castes – all gone. Everything has now been privatized. What this state has managed to do is tag you as a leftist, communist, Urban Naxal if you talk about economic issues. This is how they have taken Dalits away from a radical program.

The neoliberal agenda has to be put down on its head. It is a difficult conversation to have. I am doing it, I am pushing it, and I have got my fair share of criticism, but I’m going to keep speaking on this.

Shaunna: Why is there so much impunity when it comes to caste violence, and sexual violence, in particular, on/against Dalits?

Suraj: The idea of impunity is not a departure – it is an ingrained form of caste violence. When we think about impunity, it is part and parcel of how caste operates. It is one of the vehicles that runs the machine of caste. Because impunity is a given, the action committed – violent or non-violent -- has a free hand. [In the process,] the idea of accountability is lost. Impunity forms the bedrock for every oppression.

Impunity and accountability merge when the idea of agency comes to the fore. Impunity, in a context where the oppressor comes to enslave the Dalit woman's body, downplays the importance of the Dalit woman's agency. Agency is neutralized in caste formations. If impunity exists, then accountability has to counter it with three axioms – moral, ethical, and statutory. Currently, one can't just go rape a woman because these three axioms are working against the predators' attitude. Caste downplays all these three axioms of accountability – when I say caste, I mean untouchability.

Untouchability is the Mecca of impunity, and more than anything else, it adheres to the most vulnerable bodies. Caste makes all Dalit bodies vulnerable. In the #MeToo movement, the idea of impunity was questioned head-on, even at the level of gaze. The things that were normalized in the caste system could have been held accountable by the three axioms of accountability – ethics, morality, and statutory.

When we talk about India, the #Metoo movement has to challenge tradition, especially tradition that gives birth to all these manifestations. The story of Durga Puja is an archetype of India’s #MeToo movement. The dominant caste woman killing the Dalit, Adivasi, or Sura man. #Metoo hash taggers who have believed in this ideology don't want to come to terms with the historical vacuum that exists when it comes to documenting impunity towards untouchability. This historical vacuum has led us to think that no caste atrocity took place in this equation. With this historical vacuum, there has also been a vacuum of agency. India's #MeToo movement hasn't addressed this. This doesn't mean I am downplaying the experiences of women [who were part of #MeToo]. But if it is not self-aware, the power hierarchy [rooted in caste] would continue.

IV

DALIT FILM

Shaunna: Why did you pursue the project of a Dalit Film Festival? Why did you choose to organize it in the States, in New York?

Suraj: I took a class with Cornel West on Du Bois for an entire semester in 2016. And in that class, there was an episode where Du Bois organizes a pageant, 'The Star of Ethiopia', where he demonstrates the origins of black or African culture. It takes the audience to Ethiopia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Egypt, and he wrote somewhere in his book about tracing the richness of Black civilization. One of the reasons behind that was to say, let us not be judged by the mediocre standards of white colonial people, without necessary inventories of innovation and creation. If we confine ourselves to the white gaze, we might not be able to escape some of these problems. He wanted to deepen the historical myth and timeline of black peoples’ existence. As he referred to the black people as “the prehistoric black men who gave to the world the gift of welding iron.”

Du Bois wrote three biographies of his life. In the second one, he reflects on this experience of organizing ‘The Star of Ethiopia’. When [I read about] him staring at the stage, feeling the emotional rush and pride to see the black woman walking down it, I was like ‘damn’!! This is where the idea came to me. This is what I mentioned in my opening address to the Film Festival.

The plan was similar to Du Bois'. I wanted Dalit Art to be appreciated because many times, it is appropriated rather than appreciated. Many people think that in their appropriation, they appreciate – which is not the case. One aspect was to bring Dalit beauty and Dalit genius to the stage and give them a desirable platform. All I did was to conceive the idea and provide the platform. The audience came. I must mention the help of the volunteers at the event.

We provided the platform for highly talented and much deserving filmmakers from India. Many people are not able to see their work because of regional boundaries and the regionalism that it creates in India but Dalits in India are pan-Indian. You can find Dalits anywhere in the country, and they talk about similar values. For example, in your [Shaunna’s] Karnataka, you have MariAmmā and PochAmmā. We [in Maharastra] have different gods with the same name MarĀī, PochĀī. Ammā and Aī mean the same thing – mother. There are very nuanced cultural tangents that connect us. Now, when it comes to cinema, Tamil cinema is there and thriving, but really very few people outside Tamil Nadu really actually watch or consume Tamil cinema, unless, of course, it is specially made for a north-Indian audience or is dubbed. Then a filmmaker like Pa. Ranjith comes along and makes a film and, Bam! In my hometown, which is in Nanded in Maharashtra, the youth have Display Pictures of Ranjith's films. Similarly, Nagraj Manjule comes out with a film and easily crosses the linguistic state borders. In places like Tamil Nadu, Telengana, Kerala, and North India, folks are like, wow!

This means that this art has the potential to transcend all kinds of boundaries. Not just linguistic and geographical, but also our own historical boundaries. By looking at these experiences, I wanted to look at how Du Bois looked at the pageant.

Dalit Film Festival came about when I organized a panel at the Indian Conference at Harvard, a reputable conference and what-not. Within that, I could see that these people were the stars. Everybody wanted to click pictures with them! Mind you, Pa Ranjith speaks Tamil, Nagaraj Manjule speaks Marathi and Hindi, Niharika Singh speaks English. So we had three different individuals with three different languages, from three different castes, but with a commitment to their community. That was the beauty of it.

I bring this up to say that there is so much innovation and creativity that exists in Dalit ghettoes. They just don't get recognized. I wanted people in the world and in New York City to witness it. People came for the festival all the way from the West Coast and from Canada. Once we establish the genre of Dalit Films, just like African films, like Black Films, we would like to make it a yearly, or at least a once-in-two-years program.

I also want to have an International Dalit Literary Conference, where I want to invite people from different states across India. Each state has an amazing Dalit literary tradition. The more I learn, the more I am humbled by the breadth of it. The grasp on human emotion and the fluidity of expressing it is both, at once, heavy and light. That is the beauty of non-English Dalit literature. Through the International Dalit Literary Conference, I am hoping that we launch certain publication ventures, where we get people's writing translated into English and spread their writing around their world. If we have a press or publication in Canada or elsewhere, and we have a project of translation, the world will get to know that. This is a kind of literary politics, where we don’t have to translate thick books, but smaller essays as well. I also want to institute awards for the literary and arts world. We would like to honor the Dalit writers and artists for their amazing skills. They're protecting the community from the arrows of the opposite camps.

Posters at the Dalit Film Festival at Barnard College, New York. Source: Shaunna Rodrigues

Shaunna: One can understand how Dalit film confuses or confounds the popular gaze, but what does it do to what some call Bahujan or Dalit spectatorship?

Suraj: See, I look at the technology of cinema through Walter Benjamin's framing. Benjamin has been a very complex and, at the same time, simple figure when it comes to the motion picture. Motion picture, which was once the experience of the community, seems to have now become a personal experience, especially with people using laptops/phones to watch them – that has changed the communal logic of cinema. I remember in the 90s, our families would take Dabbas and go to the cinema and eat food. And during the Diwali holidays it was aunts, uncles, cousins. A local cinema would be booked to enjoy the fun

I would not frame it as Bahujan spectatorship simply because the ontology of Bahujan spectatorship hasn't been established. This is a political way of talking about it because if we are talking about Bahujan, then we are also talking about Shudras, and they have been dominating regional as well as the national film industry. For example, if you take Andhra, or Tamil Nadu, or Maharashtra, Shudras, or those I call ODC (Other Dominant Castes) have economically ascended to a Brahminical program, however, they know about their humiliating past, and thus, they also try to find a way to counter it. Many anti-caste cinemas from regional locales were an outcome of this realization.

If I have to talk about the spectatorship of the poor working class Dalits, and this is an academic argument, the screen filters the ideas that come to this spectatorship. After all, the cinema is monologic – you can’t talk back to the screen. That might be changing in a world in which Zoom is being used, where one could have an interactive cinema. But otherwise, this is the case. On Dalit spectatorship, Nagraj Manjule put it really well. He said whenever he saw Amitabh Bachchan as an angry young man on screen, he saw a Dalit in him. Because who are slum slum-dwelling taxi drivers? With the name Vijay? In our colony, there would be someone who would be called Sanjay, and we called him Sanjay Dutt, or there would be a guy called Vijay, and we would call him Vijay Chauhan, because of film characters!

Film was a very necessary ingredient that provided certain assurance to toiling, hardened masses. The emotional synergies of the oppressed community do not get adequately recognized. Their emotions are not valued. We don’t have frameworks to identify the tears of poor Dalits. How do you identify Dalit tears? Is it coming from emotion, trauma, repressed desires? What are the various ways of looking at it?

Spectatorship is very much shaped by how one's emotions are processed through the purifying of ideas that come through the screen. But again, Dalits did not just consume everything as it was shown in cinema. They integrated what they saw according to their own convenience. I'll give you an example: Hrithik Roshan, when he started appearing in cinema, became a big shot in the late 1990s, early 2000s. My friends in my Dalit neighborhood – ghetto – identified him as a Dalit – because he didn’t have a name like Joshi, Dixit, or Pandey. I remember my friend telling me that ‘I think he’s a Dalit man’ because he was Hrithik Roshan. A handsome man who played the story of a poor, humble background who is shy but determined. He couldn’t be anyone but Dalit for my Dalit friend. What this means is that Dalit spectators have owned that memory for themselves.

Within these films, there are comedy scenes too – usually given to those who are dark-skinned, not "very handsome" in a caricature of white tone obsessed cinema. Those scenes were reenacted in our houses because we could immediately relate to that person. Johnny Lever is a Dalit, and we could immediately relate to his acting and replicate his dialogues. We took what was necessary for our survival for our everyday life.

Cinema is not just entertainment. It is often an insult packed in entertainment. I wrote an article on Dalit Cinema a couple of years ago. In my observation after my article, I saw that various social media pages were trying to interpret certain scenes to demonstrate the problem of caste. Caste was so visible, yet it was filtered, but Dalits never misunderstood this fact. But they were always looking for a direct reference – say for Ambedkar. So Salman Khan performed this very popular song in Judwa – "East or West, India is the best," and in that song, he has a line which goes "Baba Ambedkar wah wah." Why do I remember this song so much? Because he said Baba Ambedkar Wah Wah! Can you imagine the kind of confidence it offered us? Salman Khan became a favorite among Dalits. On Wednesday evenings in Chitrhaar, a 30 30-minute song program on Doordarshan became our spot because we knew they would run this wildly popular song. And in the whole song, we knew when it was our moment—the Baba Ambedkar moment. Imagine an entire Dalit population of a few hundred million celebrating that 2-second reference.

Even today, you don't see Dalit marriages or private stories on screens. Dalit lives are presented either via Ambedkar or Phule. Apart from that, they don't exist. The cultural avenues that we have, therefore, have to proceed through Dalit film. The whole question of spectatorship has to be viewed in this way.

***

Shaunna: I think what is holding this consolidated interview together is the central question of how to view both research and politics through the lens of caste. How strongly has the obfuscation of caste, and it's subtle but pervasive forms of operation, upheld a Brahmanical order in the knowledge-making around politics in India?

Suraj: This is why the sensibility of caste is so personal. People might want to study caste but not talk about their own caste. The obfuscation was entirely a postcolonial project, four decades of scholarship after the independence (of India) was about the obfuscation of caste. These are the people who work in American academia. What this did was make Dalit entirely irrelevant, and when relevant only as a victim of the system. But Dalit is more than that. Being Dalit is about ownership of time. Dalit decides the future.

That is why people get disappointed about the Dalit or caste lens in Hindu-Muslim divide because they want to devote a whole lens to crafting their own scholarship. When you study so many centuries of rule by Muslims in India, what is relevant is to ask, why did they not abolish untouchability? Why did they not create more opportunities for Dalits to thrive? Why is there not any prominent Dalit name coming from the annals of the Mughals or Afghans or Turk Indian history? Communalism is caste – I’m not the first to make this argument. Dilip Menon has made it, as have many others. I'm rehashing this. I am not anti-Muslim. I am not anti-Hindu. I just want to prioritize the way in which we should address issues through new issues. If I said this in Nanded, nobody would have listened to me. But I’m doing it now.

I will create my own criticisms. Caste is going to be a relevant factor. Why haven’t you created a Dalit hero? When people want to say that we want to fight oppression in India, my question is, whose oppression? And why do you want to fight? That is very important. Now, people like us are coming to reclaim what was obfuscated, and it has been a difficult journey. You don't want me to have my own renaissance? You don’t want me to have my own liberation? You want to steal the moment from me when I am now ready with all the might of education, voice, beauty, intelligence, and checking all the boxes you ask of me? Yet you want to put me down?